Written by Shaoni Bhattacharya, New Scientist, 27 August 2011

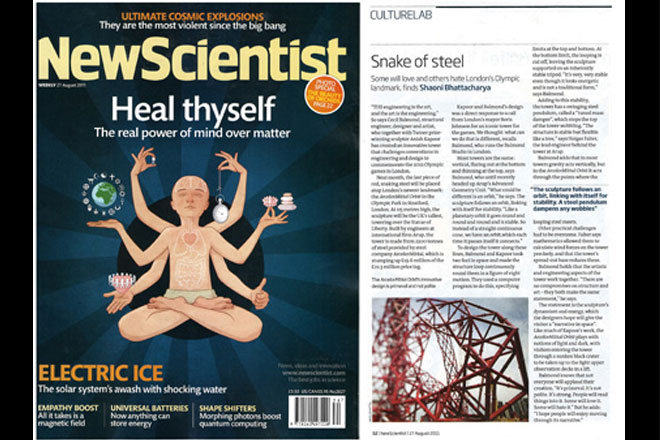

“THE engineering is the art, and the art is the engineering.” So says Cecil Balmond, structural engineer, designer and artist, who together with Turner prizewinning sculptor Anish Kapoor has created an innovative tower that challenges conventions in engineering and design to commemorate the 2012 Olympic games in London.

Next month, the last piece of red, snaking steel will be placed atop London’s newest landmark: the ArcelorMittal Orbit in the Olympic Park in Stratford, London. At 115 metres high, the sculpture will be the UK’s tallest, towering over the Statue of Liberty. Built by engineers at international firm Arup, the tower is made from 2200 tonnes of steel provided by steel company ArcelorMittal, which is stumping up £19.6 million of the £22.3 million price tag.

Kapoor and Balmond’s design was a direct response to a call from London’s mayor Boris Johnson for an iconic tower for the games. We thought: what can we do that is different, recalls Balmond, who runs the Balmond Studio in London.

Most towers are the same: vertical, flaring out at the bottom and thinning at the top, says Balmond, who until recently headed up Arup’s Advanced Geometry Unit. “What could be different is an orbit,” he says. The sculpture follows an orbit, linking with itself for stability. “Like a planetary orbit it goes round and round and round and is stable. So instead of a straight continuous cone, we have an orbit, which each time it passes itself it connects.”

To design the tower along these lines, Balmond and Kapoor took two foci in space and made the structure loop continuously round them in a figure of eight motion. They used a computer program to do this, specifying limits at the top and bottom. At the bottom limit, the looping is cut off, leaving the sculpture supported on an inherently stable tripod. “It’s very, very stable even though it looks energetic and is not a traditional form,” says Balmond.

Adding to this stability, the tower has a swinging steel pendulum, called a “tuned mass damper”, which stops the top of the tower wobbling. “The structure is stable but flexible like a tree,” says Holger Falter, the lead engineer behind the tower at Arup.

Balmond adds that in most towers gravity acts vertically, but in the ArcelorMittal Orbit it acts through the points where the looping steel meets.

Other practical challenges had to be overcome. Falter says mathematics allowed them to calculate wind forces on the tower precisely, and that the tower’s spread-out base reduces these.

Balmond holds that the artistic and engineering aspects of the tower work together. “There are no compromises on structure and art – they both make the same statement,” he says.

The statement is the sculpture’s dynamism and energy, which the designers hope will give the visitor a “narrative in space”. Like much of Kapoor’s work, the ArcelorMittal Orbit plays with notions of light and dark, with visitors entering the tower through a sunken black crater to be taken up to the light upper observation decks in a lift.

Balmond knows that not everyone will applaud their creation. “It’s primeval. It’s not polite. It’s strong. People will read things into it. Some will love it. Some will hate it.” But he adds: “I hope people will enjoy moving through its narrative.”

Source: New Scientist